Constantinople/1453

Constantinople/1453

Visit the seige

If you want to see the sites and sights of the fall of Constantinople mentioned in my book, here are some suggestions. Any good guidebook will fill in the practical details of transport and opening times – along with a very useful website www.turkeytravelplanner.com – so I’ll not dwell very much on the practicalities. Also see ‘Gallery’ for pictures and ‘Resources’ for books.

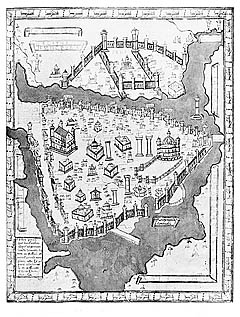

Locating the old city

Despite the explosion of Istanbul in recent decades, the layout of the old city of Constantinople/Istanbul depicted on medieval maps remains largely recognizable today, because of its site. Think of a rough triangle, bounded by water on two sides – the Sea of Marmara on one side, the Golden Horn on the other – the third side capped by the land walls, the walls of Theodosius, which still march from the Marmara to the Horn in an unbroken succession of towers. This envelope of about twelve miles is the footprint of Constantinople.

It would be handy to arm yourself with a really good map with a gazetteer. I use the EuroCity 1: 7,500 map, published by Geocenter. (Its only drawback is that, because of the shape of the city, it excludes a snippet of wall at the Marmara end.) The layers of the historical city lie so neatly on top of each other, that the main thoroughfares of Constantinople, down which Mehmet’s cavalry jingled from the walls on 29 May 1453, are still the main arterial routes today. The Horn is now capped by the Galata Bridge at its outer end, and beyond lies Galata itself, with its pointed Genoese tower still visible. Further down the Bosphorus shore, the Ottoman navy was anchored at the Double Columns, now the site of the Dolmabahçe Palace. Mehmet’s fleet was hauled into the Golden Horn at Kasımpaşa. (The starting point was on the shore probably somewhere around Tophane Iskelesi – the gazetteer will be handy if you want to follow this – up Kumbaracı Yokuşu, over Istiklal Caddesi and down the other side to Kasımpaşa: a distance of about 1 ¼ miles.

Anyway here is a range of places to sample the fall of Constantinople.

Around Haghia Sophia

Of course Haghia Sophia/Aya Sofya was the heart of Constantinople and its final death bed. The greatest space in late antiquity is still as awe-inspiring as it was in the Middle Ages. Just outside it once stood the giant equestrian statue of Justinian – long gone. This was the centre of the Byzantine world. Just opposite Haghia Sophia, at the start of Divanyolu Caddesi, stands a marble stone – the Milion, the golden milestone – from which all distances in the Byzantine Empire were measured. And of course facing the church is the Hippodrome with the surviving monuments of Constantine the Great and early emperors.

In nearby Yerebatan Caddesi is the subterranean water cistern, the Yerebatan Sarnıçı, a spooky underground world of vaulted columns resting on stone heads – one of several cisterns in the city. People took shelter in these cisterns during the final assault.

If you walk up Divanyolu Caddesi towards the Grand Bazaar you will come to the remains of the forum of Constantine and the stump of his column banded in iron and still standing (and probably wrapped in plastic or scaffolding). It was here that the Orthodox faithful hoped, in vain, that the Ottomans would be turned back by an angel with a flaming sword.

The walls

After Haghia Sophia, the great surviving remnant of Constantinople is the land walls – a breathtaking piece of military engineering – and much undervisited.

You can walk the length of the walls from end to end in a few hours (four miles). The journey will give you an extraordinary sense of the scale of the siege. Or you could break it into a couple of stages. You could use Turnbull or Van Millingen (if you’re really into it) as your guide (see Resources to download maps of the wall). Wikipedia has a good free article on the walls too.

Just a small word of caution here. Some sections of the wall are remote and rather seedy – particularly towards either end. Just to be on the safe side, if you are planning to walk it from end to end, I would suggest that you make the journey with a companion.

There are three easy ways to get to the walls from the Sultanahmet area. Further details are given below.

- Take the suburban train to Yediküle

- Take the tram to Tophane

- Take the tram to Aksaray, then change and catch the metro to Adnan Menderes

However my suggestion if you want to sample the walls in just one place or walk its whole length is to start at Yediküle.

To get to Yedikule take the little suburban train (Banlyo treni) from the main station Sirkeci – or, more convenient if you’re staying around Sultanahmet, the station at Cankurtaran – and get out at Yediküle, turn left and walk up the street for a few hundred yards and you’ll get to Yediküle itself – the seven towers – now a small museum site. This is best place to start, or to sample the walls if time is tight.

A small entrance fee gives you entrance to the section of wall containing the Golden Gate, once the imperial entrance of the Byzantine Emperors – and subsequently blocked up by Mehmet the Conqueror against prophecies of their eventual return. You can get the best sense of the depth of the moat outside this section of wall – now an impressive series of vegetable gardens. From the ramparts you get a wide view south to the Marmara, north down the line of the walls, and you can inspect some of the cannon balls fired at the walls.

From here you can follow the wall all the way down to the Horn, passing a succession of gatehouses and towers. Some sections have been rebuilt in rather alarmingly bright brick – but this may have looked authentic around 450 AD. In other places the towers are cracked and split by earthquakes and Ottoman gunfire and time. From the ramparts you can look out onto the ring road and greater Istanbul, now besieging the old city, and imagine the tents and bright banners of the Ottoman army, camped from shore to shore along the whole front.

The walk takes you past a series of ancient portals – use the maps as a guide – heavy, dark, mysterious eyelets into the ancient city that still have the power to awe the visitor – each with its own particular legend in Byzantine history. (Use Turnbull or Van Millingen to follow the route in detail.) And the wall, white limestone, with running lines of red brick, is littered with small inscriptions, crosses and initials – though some have gone since Van Millingen’s time. There’s a sense of extraordinary antiquity about this place.

If you only want to walk halfway, get out at Topkapı (Turgut Özal caddesi) and take the tram back to Sultanahmet or a little further on where the Adnan Menderes Caddesi cuts a broad hole in the structure. This is the site of the Lycus River, the most vulnerable section of the defences, and the walls here are in a particularly poor state – the work of Ottoman gunfire. At Adnan Menderes you can pick up the underground train back to Aksaray (and from there the tram back to Sultanahmet). It was opposite Topkapı (the gun gate), that Mehmet placed his huge gun, the Basilica.

Beyond lie further surprises and delights. You pass the ominous Fifth Military Gate, perhaps the place where Constantine fell and at the crest of the rise by a mosque (the Mihrimah Sultan Camii), just before Edirne Kapı, you can scramble up onto a tower and get a good view looking over the city, north to the Golden Horn and east towards the Bosphorus. It was through the Edirne Kapı that Mehmet made his triumphal entry into the city. Further on, the wall takes a sudden kink past the imposing shell of Constantine’s palace, the Blachernae, and the walls become hard to follow amongst the maze of backstreets – for which a map comes in handy. Along the way you can pass in and out of various gateways, gaze down into the gloomy prison of Anemas, scene of some unpleasant moments in Byzantine history, and walk outside the walls across open ground – where the crusaders camped before the infamous sacking of 1204 – until you reach Ayvansaray Caddesi, the busy road that flanks the Golden Horn. If you cross the road, you can pick up a boat at the Ayvansaray vapur iskelesi (ferry quay), back to the Galata bridge (hourly service) – a hugely enjoyable way of rounding off your day.

Other things to do

1. Take a boat up the Golden Horn

Take the boat up the Horn from the Galata Bridge – guide books will advise. You will stop at Kasımpaşa – the Valley of the Springs. The original chain was further out than the present Galata Bridge, but it’s a small distance from shore to shore. Looking back across the Horn from Kasımpaşa, you can get a sense of how claustrophobic the siege became once Mehmet rolled his ships into the Horn. It’s worth going up to Eyüp, a particularly holy mosque for Muslims – the burial site of Muhammad’s standard bearer, whose tomb was allegedly rediscovered after fall.

2. Visit the Kariye Müzesi (Kariye Camii Sokak, Edirnekapı)

An almost intact Byzantine church with beautiful frescoes, just behind the walls.

3. Climb the Galata Tower

Just across the Horn. The tower was the scene of a significant act of treachery during the siege. From the viewing platform you get a wonderful view over the Horn and back to the old city.

4. The military museum (Askerı Müze, Vali Konağı Caddesi, Harbiye)

A bit of a hike: a taxi ride beyond Taksim. Has a collection of Mehmet’s siege guns, the chain that was strung across the Horn, dioramas and models of the siege, weapons and armour – and performances of ferocious janissary music on certain days. (See guidebooks and Gallery pictures.)

5. Take a boat up the Bosphorus from the Galata Bridge

Hugely impressive in its own right – you’ll get a completely different perspective on the city. You’ll go past Dolmabahçe Palace (the Double Columns during the siege), Rumeli Hisarı – the Throatcutter – (see the Gallery), the castle built by Mehmet to strangle Christian trade with the Black Sea, now dwarfed by the Attaturk Bridge – and opposite it, an earlier castle Anadolu Hisarı. If you go to the last stop on the line, Anadolu Kavağı, you can eat a fish lunch and glimpse the portals of the Black Sea, the site of earlier heroic deeds – the clashing rocks that Jason and the Argonauts had to dodge on their way to the golden fleece.

6. Visit Mehmet’s tomb

At the Fatih Camii (mosque) in Islambol Caddesi. An impressive catafalque, guarded at the door by stone cannon balls, gives an impression of the status of Mehmet in Turkish history. (See Gallery picture)